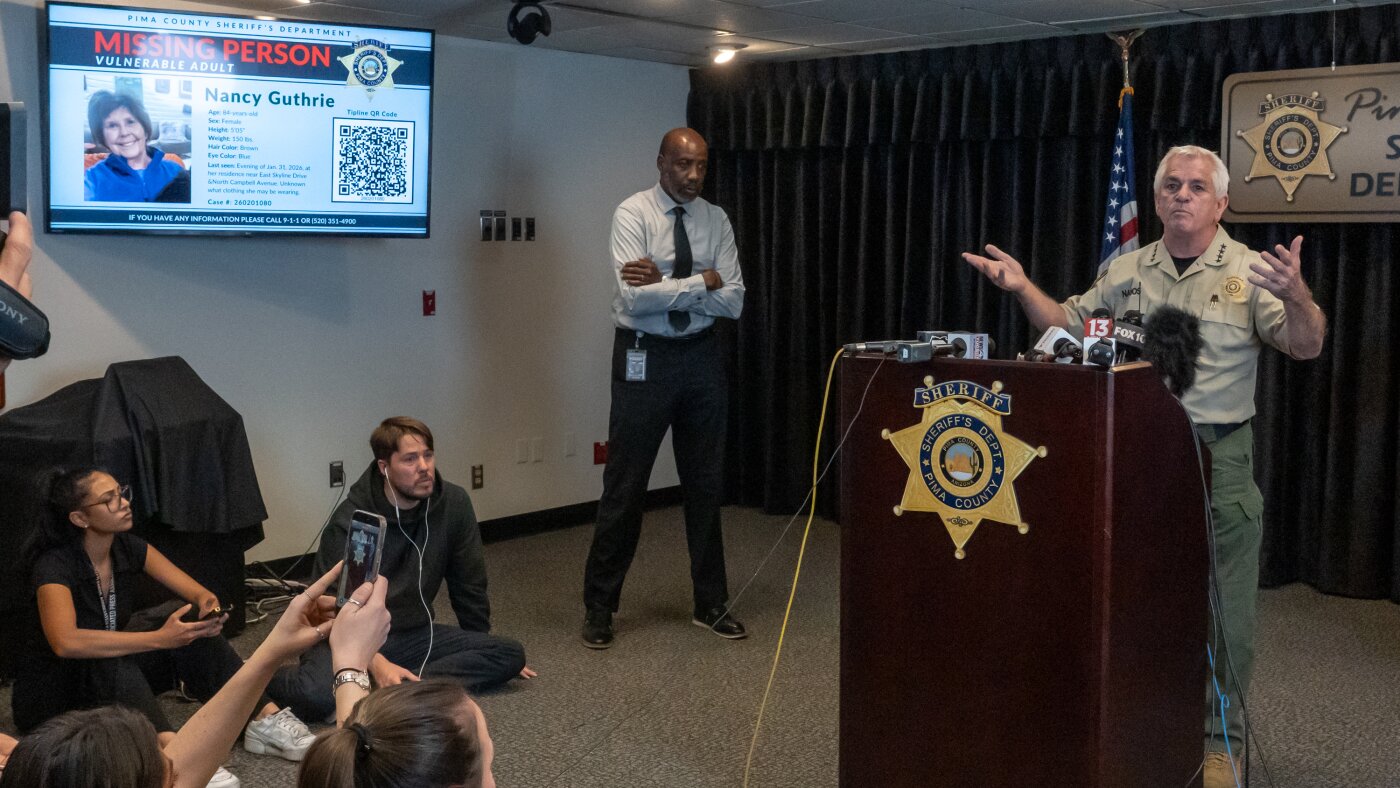

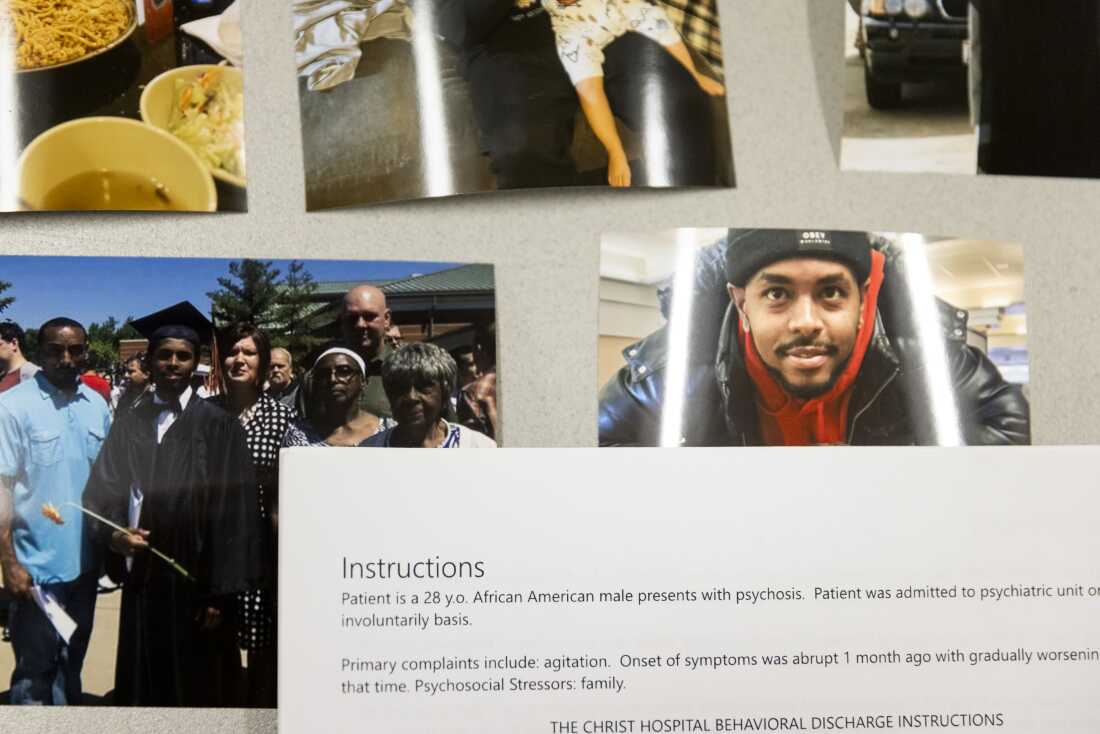

Family photos and hospital records of Quincy Jackson III, gathered by his mother, Tyeesha Ferguson. The mental health system makes it "easier to criminalize somebody than to get them help," she says. "He's not a throwaway child." Meg Vogel for The Marshall Project and KFF Health News hide caption

toggle caption

Meg Vogel for The Marshall Project and KFF Health News

SPRINGFIELD, Ohio — Tyeesha Ferguson fears her 28-year-old son will kill or be killed.

"That's what I'm trying to avoid," said Ferguson, who still calls Quincy Jackson III her baby. She remembers a boy who dressed himself in three-piece suits, donated his allowance, and graduated high school at 16 with an academic scholarship and plans to join the military or start a business.

Instead, Ferguson watched as her once bright-eyed, handsome son sank into disheveled psychosis, bouncing between family members' homes, homeless shelters, jails, clinics, emergency rooms and Ohio's regional psychiatric hospitals.

Over the past year, The Marshall Project — Cleveland and KFF Health News interviewed Jackson, other patients and families, current and former state hospital employees, advocates, lawyers, judges, jail administrators, and national behavioral health experts. All echoed Ferguson, who said the mental health system makes it "easier to criminalize somebody than to get them help."

Tyeesha Ferguson has been trying to get mental health care for her son, Quincy Jackson III, for most of his adult life. He has cycled in and out of hospitals and jails for about a decade. Meg Vogel for The Marshall Project and KFF Health News hide caption

toggle caption

Meg Vogel for The Marshall Project and KFF Health News

State psychiatric hospitals nationwide have largely lost the ability to treat patients before their mental health deteriorates and they are charged with crimes. Driving the problem is a meteoric rise in the share of patients with criminal cases who stay significantly longer, generally by court order.

Patients wait or are turned away

Across the nation, psychiatric hospitals are short-staffed and consistently turn away patients or leave them waiting with few or no treatment options. Those who do receive beds are often sent there by court order after serious criminal offenses.

In Ohio, the share of state hospital patients with criminal charges jumped from about half in 2002 to around 90% today.

The surge has coincided with a steep decline in total state psychiatric hospital patients served, down 50% in Ohio in the past decade, from 6,809 to 3,421, according to the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. During that time, total patients served nationwide dropped about 17%, from 139,434 to 116,320, with state approaches varying widely, from adding community services and building more beds to closing hospitals.

Ohio Department of Behavioral Health officials declined multiple interview requests for this article.

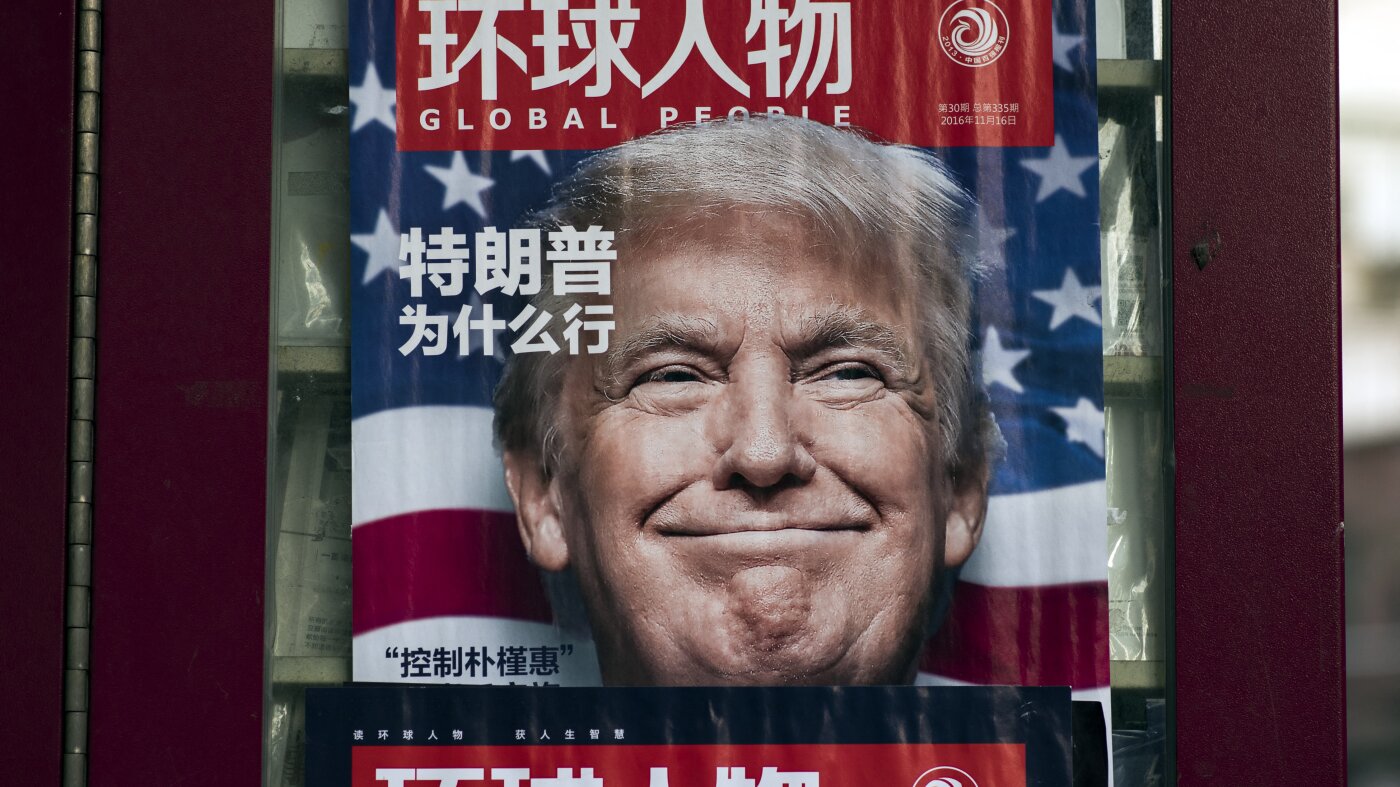

The decline in capacity at state facilities unfurled as a spate of local hospitals across the country shuttered their psychiatric units, which disproportionately serve patients with Medicaid or who are uninsured. And the financial stability of local hospital mental health services is likely to deteriorate further after Congress passed President Donald Trump's One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which slashes nearly $1 trillion from the federal Medicaid budget over the next decade.

The constricted flow of new patients through state hospitals is "absolutely" a crisis and "a huge deal in Ohio and everywhere," said retired Ohio Supreme Court Justice Evelyn Lundberg Stratton. As co-chair of the state attorney general's Task Force on Criminal Justice and Mental Illness, Lundberg Stratton has spent decades searching for solutions.

"It hurts everybody who has someone who needs to get a hospital bed that's not in the criminal justice system," she said.

"I'm sick; I take medication"

Quincy Jackson III's white socks stuck out of the end of a hospital bed as police officers stood watch.

At 5-foot-7-inches, Jackson has a stocky build and robotic stare. Staff at Blanchard Valley Hospital in Findlay, Ohio, had called for help, alleging Jackson had assaulted a security guard.

"I'm sick; I take medication," Jackson said to the officers, according to law enforcement body camera footage. His hands were cuffed behind his back as he lay on the bed, a loose hospital gown covering him.

Ferguson called it one of his "episodes" and said her son experienced severe psychosis frequently. In one incident, she said, Jackson "went for a knife" at her home.

From December 2023 through July 2025, Jackson was arrested or cited in police reports on at least 17 occasions. He was jailed at least five times and treated more than 10 times at hospitals, including three state-run psychiatric facilities.

A recent psychiatric evaluation noted that Jackson has been in and out of community and state facilities since 2015.

Jackson is among a glut of people nationwide with severe mental illness who overwhelm community hospitals, courtrooms, and jails, eventually leading to backlogs at state hospitals.

High-profile incidents

That dearth of care is often cited by families, law enforcement authorities, and mental health advocates after people struggling with severe mental illness harm others. In the past six months, at least four incidents made national headlines.

In August, a homeless North Carolina man reportedly diagnosed with schizophrenia fatally stabbed a woman on a train. Also in August, police said a Texas gunman with a history of mental health issues killed three people, including a child, at a Target store. In July, a homeless Michigan man who family members said had needed treatment for decades attacked 11 people at a Walmart store with a knife. In June, police shot and killed a Florida man reportedly diagnosed with schizophrenia after authorities said he attacked law enforcement.

Mark Mihok, a longtime municipal judge near Cleveland, told a spring gathering of judges and lawyers he had never seen so many people with serious mental illnesses living on the streets and "now punted into the criminal justice system."

37-day wait for a bed

At Blanchard Valley Hospital, sheriff's deputies had taken Jackson from jail for a mental health check. But Jackson's actions raised concerns.

In the body camera video, a nurse said Jackson was "going to be here all weekend. And we're going to be calling you guys every 10 minutes."

The officer responded: "Yeah, well, if he keeps acting like that, he's going to go right back" to the county jail.

Within minutes, Jackson was taken back to jail, yelling at the officers: "Kill me, motherf-----. Yeah, shoot them, shoot them. Pop!"

Statewide, Ohio has about 1,100 beds in its six regional psychiatric hospitals. In May, the median wait time to get a state bed was 37 days.

That's "a long time to be waiting in jail for a bed without meaningful access to mental health treatment," said Shanti Silver, a senior research adviser at the national nonprofit Treatment Advocacy Center.

Long waits, often leaving people who need care lingering in jails, have drawn lawsuits in several states, including Kansas, Pennsylvania, and Washington, where a large 2014 class action case forced systemic changes such as expanding crisis intervention training and residential treatment beds.

Ohio officials noticed bed shortages as early as 2018. State leaders assembled task forces and expanded treatment in jails. They launched community programs, crisis units, and a statewide emergency hotline.

Yet backlogs at the Ohio hospitals mounted.

Ohio Department of Behavioral Health Director LeeAnne Cornyn, who left the agency in October, wrote in a May emailed statement that the agency "works diligently to ensure a therapeutic environment for our patients, while also protecting patient, staff, and public safety."

"It's heartbreaking"

Eric Wandersleben, director of media relations and outreach for the department, declined to respond to detailed questions submitted before publication and, instead, noted that responses could be publicly found in a governor's working group report released in late 2024.

Elizabeth Tady, a hospital liaison who also spoke to judges and lawyers at the May gathering, said 45 patients were waiting for beds at Northcoast Behavioral Healthcare, the state psychiatric hospital serving the Cleveland region.

"It's heartbreaking for me and for all of us to know that there are things that need to be done to help the criminal justice system, to help our communities, but we're stuck," she said.

Ohio officials added 30 state psychiatric beds by replacing a hospital in Columbus and are planning a new 200-bed hospital in southwestern Ohio.

Still, Ohio Director of Forensic Services Lisa Gordish told the gathering in Cleveland that adding capacity alone won't work.

"If you build beds — and what we've seen in other states is that's what they've done — those beds get filled up, and we continue to have a waitlist," she said.

Heartland Behavioral Healthcare in Massillon, Ohio, is one of the state's psychiatric hospitals. Meg Vogel for The Marshall Project and KFF Health News hide caption

toggle caption

Meg Vogel for The Marshall Project and KFF Health News

This year, Jackson waited 100 days in the overcrowded and deadly Montgomery County jail for a bed at a state hospital, according to jail records.

Ferguson said she was afraid to leave him there but could not bail him out, in part, she said, because her son cannot survive on his own.

"There's no place for my son to experience symptoms in the state of Ohio safely," Ferguson said.

Sick system

Patrick Heltzel got the extended treatment Ferguson has long sought for her son, but he stabbed a 71-year-old man to death before getting it.

The 32-year-old is one of more than 1,000 patients receiving treatment in Ohio's psychiatric hospitals.

"People need long-term care," Heltzel said in October, calling from inside Heartland Behavioral Healthcare, near Canton, where he has lived for more than a decade after being found not guilty by reason of insanity of aggravated murder. Inpatient care, he said, helps patients figure out what medication regimen will work and deliver the therapy needed "to develop insight."

As he spoke, the sound of an open room and patients chatting filled the background.

"You have to know, 'OK, I have this chronic condition, and this is what I have to do to treat it,'" Heltzel said.

Patrick Heltzel with his dog, Violet, during a family visit in October 2023. (Jan Dyer) Jan Dyer hide caption

toggle caption

Jan Dyer

As the ranks of criminally charged patients in Ohio's hospitals have increased over the past decade, the shift has had an impact on patient care: The hospitals have endangered patients, have become more restrictive, and are understaffed, according to interviews with Heltzel, other patients, and former staff members, as well as documents obtained through public records requests.

Escapes and a lockdown

Katie Jenkins, executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness Greater Cleveland, said the shift from mostly civil patients, who haven't been charged with a crime, to criminally charged patients has changed the hospitals.

"It's hard in our state hospitals right now," she said. Unfortunately, she said, patients who have been in jail bring that culture to the hospitals.

In the first 10 months of 2024, at least nine patients escaped from Ohio's regional psychiatric hospitals — compared with three total in the previous four years, according to state highway patrol reports.

In one instance, two female patients at Summit Behavioral Healthcare near Cincinnati escaped after one lunged at a staff member. In another, a man broke a window and climbed out. Most of the escapes, though, were not violent.

Days after a patient at Northcoast jogged away during a trip to the dentist in a Cleveland suburb, state officials stopped allowing patients to leave any of the six regional hospitals.

A memo to leaders at the hospitals said officials had seen "similarities across multiple facilities," raising significant concern about "ensuring patient and public safety."

For Heltzel, the inability to go on outings or to his mother's house on the weekends was a setback for his treatment. In 2024, when the lockdown began, he had more freedom than most patients at the psychiatric hospitals, regularly leaving to go to the local gym and attend off-site group therapy.

His mother signed him out each Friday to go home for the weekend, where he drove a car and played with his 2-year-old German shepherd, Violet. On Sundays, Heltzel was part of the "dream team" at church, volunteering to operate the audio and slides.

Federal records reveal that, at Ohio's larger state-run psychiatric hospitals, including Summit and Northcoast, patients and staff have faced imminent danger.

In 2019 and 2020, federal investigators responded to patient deaths, including two suicides in six months at Northcoast. One hospital employee told federal inspectors, "The facility has been understaffed for a while and it's getting worse," according to the federal report. "It is very dangerous out here."

Disability Rights Ohio, which has a federal mandate to monitor the facilities, filed a lawsuit in October against the department. The advocacy group, alleging abuse and neglect, asked for records of staff's response to a Northcoast patient who suffocated from a plastic bag over their head. At the end of October, the court docket showed the parties had settled the case.

Retired sheriff's deputy Louella Reynolds worked as a police officer at Northcoast for about five years before leaving in 2022. She said the increase in criminally charged patients meant the hospitals "absolutely" became less safe. Her hip still hurts from a patient who threw her against a cement wall.

Reynolds said officers should be able to carry weapons, which they don't, and that more staff are needed to handle the patients. Mandatory overtime was common, she said, and often staff would report to work and not "know when we would get off."

A disaster that wasn't averted

Back at Heartland, Heltzel requested conditional release. The judge denied the release request.

Heltzel said it was devastating. He grew up Catholic and said, "I was kind of looking for absolution."

Now, Heltzel said he is practicing acceptance. "Acceptance is all the more important to practice when you don't agree with something," Heltzel said, adding, "I'm a ward of the state."

He still hopes to be released: "I just do what I can to move forward."

Heltzel, like Jackson, had been hospitalized before and released. In early 2013, Heltzel said, he asked his dad to kill him.

"And he refused and I did smack him," he said.

Heltzel was sent to Heartland for a short stay — about 10 days, according to his mother, Jan Dyer. She recalled "begging" the hospital staff to keep him.

Heltzel said he remembers not being ready to leave: "I was still sick, and I was still delusional."

Back at home, he said, he had a "sense of existential dread, like that all this horrible stuff was going to happen." He stopped taking his medication.

Within weeks, Heltzel killed 71-year-old Milton A. Grumbling III at his home, placing him in a chokehold and stabbing him repeatedly, according to court records. He beat him with a remote control and then left, taking a Bible from the home, as well as a ring. Delusional with schizophrenia, Heltzel believed that Grumbling had sexually abused him in another life, according to the records.

A family member of the man he killed told the judge in 2023 that Heltzel should "stay in prison," according to court records.

In denying his conditional release, judges cited Heltzel's failure to take medication before killing Grumbling.

Jenkins, who said she worked at a state hospital for nine years before becoming the lead advocate for NAMI Greater Cleveland, said psychiatric medications can take as long as six weeks to become fully effective.

"So clients aren't even getting stabilized when they're being hospitalized," Jenkins said.

'He's not a throwaway child'

In a July interview, Jackson said inconsistent care or unmedicated time in jail "worsens my symptoms." Jackson was on the phone during a stay at a state psychiatric hospital.

Tyeesha Ferguson looks through police reports, court files, and hospital records for her son, Quincy Jackson III. Meg Vogel for The Marshall Project/KFF Health News) hide caption

toggle caption

Meg Vogel for The Marshall Project/KFF Health News)

Without medicine, "my head hurts, to be honest," Jackson said, before asking to get off the phone because he was hungry. It was lunchtime. "Can you get the information from my mom?" Jackson said. "She has the records."

After Jackson hung up the phone, Ferguson explained that "he says the food is excellent, so he does not want to miss it." And, she added, the hospital staff had not yet seen the explosive side of her son.

In early September, after 45 days at Summit — his longest stay yet at a state psychiatric hospital — Jackson returned to the Montgomery County jail facing misdemeanor charges because of an altercation in April with staff at a Dayton behavioral health hospital. In court, Ferguson said, her son struggled to explain to the judge why he was there. On a video call from the jail days later, she saw him playing with his hair and ears.

"That tells me he's not OK," Ferguson said.

Before Jackson's diagnosis more than a decade ago, Ferguson said, her son wasn't a troublemaker. He had goals and dreams. And he's still "loved and liked by a lot of people."

"He's not a throwaway child," she said.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues.

The Marshall Project - Cleveland is a nonprofit news team covering Ohio's criminal justice systems.

1 month ago

39

1 month ago

39